The best bad song I ever heard

July 6, 2018 4:17 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentBy David Tucker, Communications Analyst, GFDRR

Interview with Climate Music Project founder Stephan Crawford.

I’ve never been more moved by such a jarring cacophony of music.

Closing the second day of the 2018 Understanding Risk Forum, I was treated to a performance by the Climate Music Project – a collaborative of scientists and gifted musicians that have come together to leverage music as an instrument for communicating climate risk.

I was skeptical. After all, when it comes to galvanizing action to protect the planet, one barrier is that the risks of climate change are not always easy to communicate. Layered in technical details and fraught with uncertainty about the timing and intensity of climate change impacts, the science behind climate change can get very complicated. At the same time, the long-term horizon by which some of the worst impacts of climate change are projected to occur means that the changing climate may not be immediately tangible to many people. How could something as conceptually divorced from climate science as music possibly tell that story? My skepticism soon turned into curiosity.

The music began with a calm, steady melody, accompanied by the smooth, vivid lines of various graphs slowly waltzing across a large screen behind the performers. Their symphony was set to the tempo of fluctuations in carbon dioxide levels, global temperature, and earth-energy balance – three variables commonly used to track climate change – over five centuries.

As the song reached the “present day”, it was startlingly and increasingly interrupted by jagged notes – like that unmistakable sound of a pianist’s finger accidentally hitting the wrong key. Before long, the harsh sounds outnumbered the beautiful ones, and I could hardly stand to listen any more. Behind the musicians, the charts were now every bit as frenetic as the song. And it became clear what I was listening to: the degradation of our environment, and the dangers that climate change poses to future generations if we don’t take decisive action.

Based in San Francisco, California, the Climate Music Project pens and performs musical compositions, based on climate data, which are designed to communicate the urgency of climate change to audiences around the world.

“What we do is we take climate science and through music, we make it visceral and palpable and then drive change,” explains founder Stephan Crawford.

We had the opportunity to interview Crawford – and catch a snippet of their live concert – at the 2018 Understanding Risk Forum in Mexico City, hosted by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) and the World Bank. I encourage you to give it a listen – it may be the most important “bad” song you ever hear.

RELATED:

Coping with disasters: advancing disaster risk financing strategies in the Caribbean

May 31, 2018 9:29 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentAuthors: Xijie Lu, Mary Boyer, Kerri Cox, Rashmin Gunasekera

In a few weeks, hurricane season in the Caribbean will begin again. In our travels to Belize, the British Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Saint Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines over the past two months, we’ve heard variations of this same refrain. People in these islands are talking about what they will do differently this season, from conducting community-wide drainage cleanups to stockpiling cash in the event of island-wide power outages; whilst at the national level, ministries are also discussing the best ways to reduce the impact of disasters going forward.

These dialogues and adjustments at the individual, community and national levels are a necessity, as over the last 40 years, disasters in the Caribbean have almost tripled. During the 2017 hurricane season, Hurricanes Maria and Irma caused unprecedented damage across several islands in the Caribbean, prompting payouts from the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility of over USD 50 million to member countries that year. Although last year was a particularly horrible season for the region, every year, at least one country in the region is hit by a strong hurricane, and ever-present threats exist like flooding, earthquakes and droughts. Although Caribbean countries have made great progress in reducing poverty and inequality over the years, disasters like these threaten to drive vulnerable populations back into poverty.

So, how can these countries cope with these disasters? One solution involves incorporating disaster risk management principles into development planning by: identifying the countries’ disaster risk; working to reduce this risk; actively preparing for disasters; implementing disaster risk financing mechanisms; and reconstructing in resilient ways.

Over the past three years, our Disaster Risk Management team in the World Bank’s Latin American and Caribbean region worked with four countries to improve one of these key areas – Disaster Risk Financing.

Well-designed disaster risk financing strategies are developed before a disaster strikes, integrated into core public finance systems, and combine risk retention and transfer instruments in the context of an effective legal framework. Utilizing funding received from the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), our team collaborated with the Ministries of Finance in Belize, Grenada, Jamaica and Saint Lucia to design cost-effective, tailored strategies that would help each country improve their fiscal resilience to disasters. This process entailed:

- Quantifying countries’ contingent liabilities to estimate the fiscal risk of natural disasters;

- Reviewing their existing systems for public financial management of disasters as well as their legal frameworks for addressing shocks;

- And evaluating the domestic non-life insurance market in each country to determine their capacity to build strong financial sectors for public and private risk transfer.

Conducting these steps collaboratively with the governments helped them to gain a much better understanding of their exposed assets and fiscal risk. For instance, in Jamaica, we estimated that the government would need to cover losses of approximately USD 121 million annually, the equivalent of 0.85% of their 2015 GDP, to address the impacts of hurricanes and floods. With a tangible risk level handy, the governments are then better equipped to assess whether existing financial protection instruments are adequate.

At the end of the process, we identified existing disaster risk financing gaps and corresponding tailored solutions for each of the four countries. These solutions were identified by the Ministries of Finance as key priority areas for improvement in the short, medium and long-term, which include:

- Creating an inventory of public assets and streamlining damage and loss data collection

- Approving a disaster risk financing strategy and streamlining reporting of post-disaster expenditures

- Establishing a contingency reserves fund, engaging external development partners in establishing contingent financing arrangements, and developing a disaster risk insurance program for key public assets, in partnership with the private insurance industry

- Promoting government and the private sector partnership to implement flexible Social Protection systems; improve the availability and affordability of private and residential catastrophe insurance; and enhance the availability of agricultural insurance.

We further developed reports for each country that detailed these recommendations for strengthening their disaster risk management strategies.

During the launch of these reports at the 2018 Understanding Risk Forum held in Mexico City, Sameh Wahba, Director of the World Bank’s Social, Urban, Rural, and Resilience Global Practice, noted, “This is the first report series published after the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season that highlights specific recommendations to strengthen disaster risk finance strategies in the Caribbean. However, for these strategies to be beneficial, countries need to foster a data-rich environment and ensure that enabling legal and policy frameworks exist.”

Indeed, the effectiveness of each country’s disaster risk financing strategy will be based on the extent to which these recommendations are implemented and how well they work together with the other components. Our team will provide support to these countries in implementing the strategies and, at the request of Governments, will also work to expand this technical assistance program to other countries in within the Caribbean region.

Revolutionizing Disaster Risk Finance: Are You Up for The Challenge?

May 23, 2018 3:41 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentApply to the third round of the Challenge Fund by June 30th!

The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), the World Bank, the UK Department for International Development (DFID), and the Centre for Global Disaster Protection, have launched a new Challenge Fund window to pilot the development of innovative risk financing mechanisms, and align global innovation with on-the-ground user needs.

Developing countries are often the hardest hit by natural disasters such as floods, cyclones, droughts and earthquakes, yet they are the most sensitive to the budget volatility caused by major catastrophes, and are least equipped to prepare for extreme events.

Financing is at the core of any disaster management action, whether risk reduction, preparedness, financial protection, or resilient recovery. Unfortunately, financing after a disaster is often long delayed, increasing the human impact.

“The application of new technologies could revolutionize financial mechanisms, for example by better targeting funds to vulnerable communities” said Francis Ghesquiere, Head of the GFDRR Secretariat. “These innovations include forecast based mechanisms that can fund early-action before a disaster strikes, or big data and machine-learning algorithms that can improve the speed at which we assess the impact of an event and accelerate payouts. The real challenge is bringing together the technical experts working on these approaches, with the experts implementing crises response programs, and at-risk communities in affected countries.”

This Challenge Fund will support projects that help bring these communities together and strengthen financial resilience in developing countries. This round is a partnership between the Department for International Development, the Centre for Global Disaster Protection, the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, and the World Bank’s Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance Program. It is launched in association with the program alliance of the InsuResilience Global Partnership. It builds on the success of previous rounds focused on risk identification.

As such, the Challenge Fund seeks to pilot new approaches to support disaster and climate risk management in developing countries by encouraging “positive disruptive” innovation and non-traditional partnerships between technology institutions, academia, private sector, international organizations, NGOs and user groups.

Interested applicants will respond to challenges including: implementation of early-action mechanisms into disaster risk financing (DRF) instruments, use of big data and machine learning to revolutionize DRF mechanisms, and application to largely untapped risks such as food insecurity. This Challenge Fund window will provide up to 5 successful projects with funding ranging from US$ 100,000-200,000 to design and implement ground-breaking solutions to address such challenges.

Details about the Challenge Fund and the submission portal can be found here.

About the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery

The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) helps high-risk, low-income developing countries better understand and reduce their vulnerabilities to natural hazards, and adapt to climate change. Working with over 400 partners—mostly local government agencies, civil society, and technical organizations—GFDRR provides grant financing, on-the-ground technical assistance to mainstream disaster mitigation policies into country-level strategies, and a range of training and knowledge sharing activities. GFDRR is managed by the World Bank and funded by 25 donor partners.

Comunicado de Prensa: Las tecnologías disruptivas ayudan a mejorar la prevención de riesgos

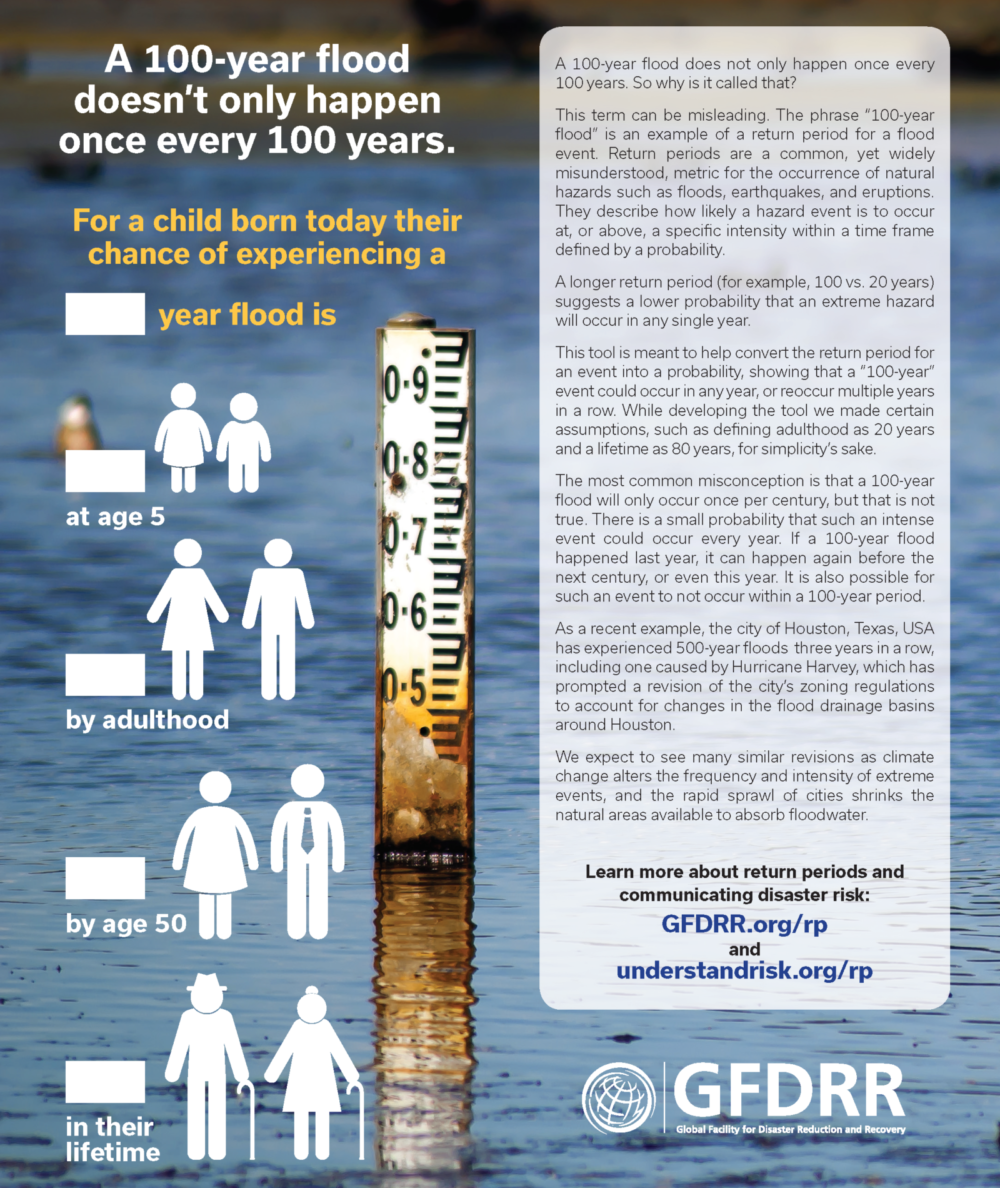

May 18, 2018 8:37 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentReturn Period Calculator

May 17, 2018 8:31 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentVisit GFDRR.org/rp to use the Return Period Calculator tool

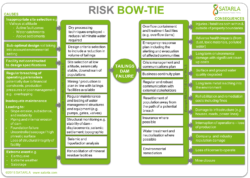

Learning from business – Risk bow-ties

May 7, 2018 7:19 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentBy Sarah Gordon, PhD, Satarla

Session lead for Tying the Knot

A risk bow-tie is a visual method through which all key knowledge regarding a risk can be portrayed on a single page. Bow-ties allow discussions and decisions to be made in an objective and rapid manner by organisations that use them. This is especially useful when knowledge needs to be collected from a range of specialists and communicated in a coherent, integrated manner.

Originally used as an incident investigation tool, risk bow-ties are now used real-time in workshops to help organisations prepare for future opportunities or threats to their business objectives. It is possible to capture the essence of a risk in just 5 minutes, using the framework to structure more detailed analysis.

Used around the world in diverse contexts, risk bow-ties have helped many different organisations better understand their risks. We see a critical opportunity for this tool to help improve the understanding of disaster risk as well.

Bow-ties don’t always have to use sticky notes (but they don’t hurt)! They can also be recorded and used to communicate the key facets of a risk to a broader audience. For example, Fig. 2 shows the causes, controls, and consequences for the failure of a waste facility in the mining industry, commonly known as a Tailings Dam. This example has been used to educate governments, the general public, and those working in mining about the reality of this risk.

Tailings dam: The requirement for tailings dams pose a significant risk to the mining industry and all those connected with such facilities, be they communities, governments, or the companies themselves. The failure of the Bento Rodrigues tailings dam on the 5th November 2015 in Brazil (Samarco) resulted in 17 lives being lost and 60 million m3 iron waste being released into the Doce River. To date 21 Directors of the company have been charged with homicide and the estimated cost to the owners is $43 Billion.

Bow-ties for Disaster Risk

In an interactive session at the 2018 Understanding Risk Forum, Satarla will lead participants through an introduction and activity applying the risk bow-tie method in a disaster risk scenario. The goal is to explore how the disaster risk identification community can learn from and implement this business strategy. Learn more about the session, and UR2018 here!

Learning from big innovations in small island states

May 4, 2018 6:56 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentBy Devan Kreisberg, Naraya Carrasco, Denis Jordy, and Alessio Giardino

If we’ve learned anything from our modern era, it’s that the smallest changes can be extremely powerful. From DNA molecules to microprocessors, “small” can have a big impact.

The same is true of the world’s small island developing states (SIDS), which account for less than 1% of the world’s population. They are also some of the world’s most vulnerable countries to disasters and climate change. Of the countries with the highest disaster losses relative to GDP, two-thirds are small island states, with annual losses between one and nine percent of GDP on average.

Even those numbers are misleading, however, since a single disaster can cripple an island’s entire economy. Without tropical cyclones, for instance, Jamaica’s economy could have grown by as much as 4% per year; instead, over the past 40 years, it has grown 0.8% annually. Sometimes, growth is wiped out all at once: When Hurricane Maria struck Dominica last year, it caused damages and losses equivalent to 220% of the country’s GDP.

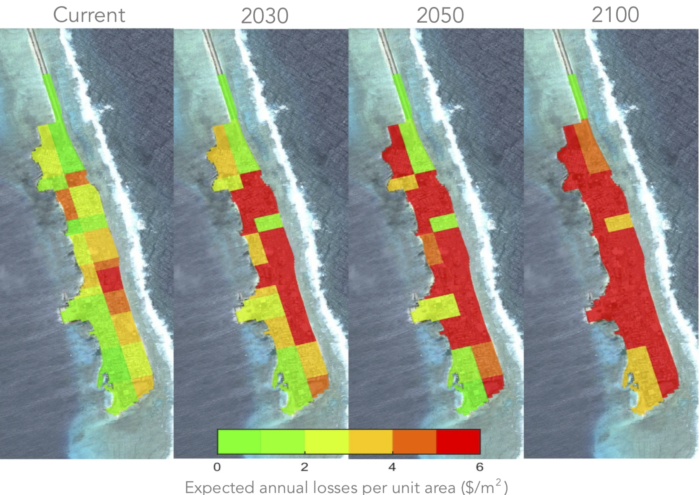

Climate change and sea-level rise will not help the situation. In the Marshall Islands, for instance, the number of people affected by disaster every year may double by the end of the century, and expected annual damages could increase by a factor of three or four. If sea levels rise by just one meter, the Maldives will disappear entirely.

But what we learn from these small, remote, highly exposed islands could be useful for millions of people around the world.

Though their size makes SIDS vulnerable, it also makes them ideal for piloting comprehensive analytical tools and innovative methodologies that help us understand climate and disaster risks and design resilience strategies. Successful tools and methodologies can later be applied to bigger countries or broader regions with similar challenges, particularly coastal areas.

For instance, a local-level, multi-hazard risk assessment on Ebeye Island in the Marshall Islands modelled the impact of flooding, erosion, and sea-level rise across the island. Using an innovative method, it also analyzed the efficacy of intervention options – a method that could be scaled up to other coastal countries.

In Tuvalu, which relies on imports, a local-level study is determining the best place to build the country’s first shipping port by analyzing everything from wave patterns to long-term climate outlooks. These techniques, too, have broader applications.

On the national level, a first-of-its-kind Climate Vulnerability Assessment in Fiji piloted a methodology to assess climate and disaster vulnerability, and to design strategies that will help the country adapt to climate change and manage disaster risk. The report, which was supported by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) and the World Bank, will inform Fiji’s development decisions for the next decade. The assessment took into account not just reduction of economic losses, but also the impact of disasters on people’s wellbeing, and led to a comprehensive, climate-resilient investment plan that covers all economic sectors.

Fiji isn’t the only country that can benefit from a risk assessment that helps plan for next 10 years. The team that developed the methodology is modifying it to be replicated in other islands, and applied to larger countries. When complete, it will be an adaptable, flexible methodology that will help governments figure out their current vulnerabilities, the actions they should take to address those vulnerabilities, and their resilience priorities.

The experiences of Fiji, the Marshall Islands, and Tuvalu – all of which show how SIDS can serve as the testing ground for bold new ways to analyze disaster and climate risk – will be discussed during the upcoming 2018 Understanding Risk Forum in Mexico City, at a technical session hosted by GFDRR, Deltares, and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. The session will showcase methods and results from several recent risk analyses that helped SIDS make informed development and resilience decisions, and discuss how they can be applied around the world.

These case studies show how a smart combination of global data, local information, and adaptive approaches can produce powerful tools – tools that generate the vital risk information that allows decision-makers to build their country’s resilience. But above all, they show the rest of the word the value of helping strengthen the resilience of SIDS, the most risk-exposed nations on the planet.

As Enele Sopoaga, the Prime Minister of Tuvalu, put it, “If we save Tuvalu, Tuvalu will save the world.”

Now that’s the power of small.

The “Small Islands: Innovations in understanding risk” technical session will take place from 11:15 – 12:45 on May 18, during the 2018 Understanding Risk Forum at the Palacio de Minería in Mexico City.

Forewarned and Forearmed

May 4, 2018 4:35 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentBy Helen Ticehurst and Nyree Pinder (Met Office), Catalina Jaime (Red Cross Climate Centre), Shristi Vaidya (Deltares), Emily Wilkinson (ODI)

Session leads for Forewarned and Forearmed

Related Pages

Weather and climate information – which predicts conditions days, months, seasons and years in advance – helps governments, businesses and the public make informed decisions to increase their prosperity, enhance wellbeing, and avoid risk.

Forecasting science and skill are constantly evolving. Supercomputers crunch trillions of calculations a second and experts turn weather data from around the world into global forecast and climate models. As their combined ability to process more and more data improves, so will forecast accuracy.

However, even the most accurate forecast has absolutely no value unless it is used to guide decisions that lead to action. This is often the trickiest bit…

Impact Based Forecasting has emerged in recent years as a technique to communicate the impacts weather has on people, their livelihoods and property in order to help decision makers mitigate impacts and prepare effectively for potential emergencies. Essentially, they focus on what the weather will do over what the weather will be.

The type of weather or hazard and the thresholds for action will vary. The core benefit of impact based forecasting is that it involves the user at every point in the design, development and delivery of the forecast. It is a collaborative process incorporating hazard, exposure and vulnerability information to establish what the impact will be. An in-depth risk analysis explores who, when and how people and assets might be affected.

Within the resilience conversation, there is recognition that acting in advance saves lives and money. Predictive capability can be used to support early action through forecast-based financing (FbF), forecast-based action (FbA), shock responsive social protection, and insurance.

Forecast-based financing uses impact-based forecasts to trigger funding to implement early actions in the window of opportunity between the forecast and the potential disaster, which can mitigate risks and prepare for effective response. Thereby, reducing the impact of that shock on vulnerable people, their livelihoods, and health, improving the effectiveness and costs of emergency response and recovery efforts. FbF/FbA mechanisms have a number of characteristics that differentiate them from other anticipatory approaches to reducing the impacts of severe weather and climate events:

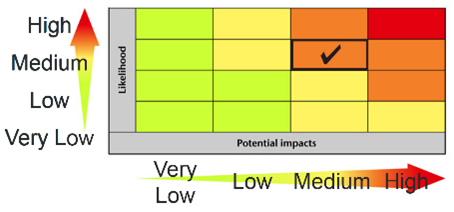

- Forecast-based Financing and Action mechanisms strive to link weather and climate forecasts to vulnerability and exposure information as well as other indicators of human wellbeing. While some of these links are obvious, such as the use of flood risk maps, others involve sophisticated analysis and tools such as impact-based forecasts or climate and food security analyses. FbF is a risk-based decision making tool. Since Weather and Climate forecasts are probabilistic, it is critical to communicate the uncertainty of forecasts whilst enabling decision makers to understand the likelihood of an event occurring.

- Forecast-based Financing and Action tools are used to trigger mitigation and preparedness for response actions designed to reduce the impact of climate hazards as they manifest. For example, Forecast-based Financing has been used by the Bangladesh Red Crescent and the German Red Cross to distribute cash before expected floods. In this instance, an impact evaluation showed that early financing helped families avoid using high-interest loans to cover basic expenses whilst preparing for the worst. During El Niño, when the risk of drought is high, The World Food Program, the Zimbabwean Ministry of Agriculture and the Food and Agriculture Organization help farmers switch to drought tolerant crops.

- Forecast-based Financing is proposing a radical shift in Disaster Financing Management to enable funding to be activated based on a forecast. Current Disaster Risk Management systems only enable funding activation for long-term interventions, or after a disaster has already occurred, which unreasonably delays action by governments, humanitarian organizations and communities.

Impact-based forecasting can support these mechanisms to define actions and thresholds for taking action, based on an acceptable level of risk or uncertainty.

National capacity for Impact Based Forecasting must be developed in order to implement national forecast based early action plans. National Meteorological Services (NMS) can be key to this if they position themselves (with government support) as a trusted and authoritative source of weather and climate information. Engaging with users is central to impact-based forecasting, and the NMSs must plan from the start to have the capacity, resources and time to engage users on a continuous basis.

When NMSs, DRR departments, civil contingencies teams, social protection programs, Red Cross Red Crescent societies, NGOs (and many others!), are mandated to work together and share data, meaningful early action can be taken. Cooperation is key to the decision-making process for early action, including understanding who will implement and when. Agencies must agree on how to communicate the uncertainty in forecasts with confidence, consistency and authority.

Impact Based Forecasting and its application in Forecast Based Early Action represents a channel to ensure that advances in forecasting and climate science can translate to actions that can enhance prosperity and save lives.

Flying robots: Using UAVs to Understand Disaster Risk

April 27, 2018 3:20 pm Published by Simone Balog-Way gmail Leave a commentBy Darragh Coward, World Bank Group

Related Pages

The threat of climate-related disasters is on the rise. In 2017 alone, economic losses from global disasters amounted to an estimated $330 billion (nearly double those of 2016). Under the weight of added pressure from rapid urbanization and population growth, many communities are increasingly vulnerable to climate-related disasters. This vulnerability, however, is being combated by major innovations aiming to transform assessment, mitigation, and response tactics in disaster risk management (DRM). The early adopters and champions of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), or drones, have been at the forefront of this transformative movement.

Through dedicated efforts by tech enthusiasts and humanitarians across the globe, the UAV industry is shifting away from its initial focus on defense applications towards a comprehensive diversification of its benefits. Within the realm of Disaster Risk Management, use cases from Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, and Latin America are actively demonstrating the incredible value of drones for addressing critical information gaps.

Disaster Risk Management is data hungry

It is commonly understood that risk assessment requires high-resolution data, which is generally expensive and complex to collect. Traditional methods for equivalent acquisition have relied on multiple tools, actors, and platforms, and have often delivered less-than-satisfactory results. With the introduction of UAVs into the DRM world, however, high-quality data with exceptional accuracy for multiple purposes is more accessible than ever before. This is largely due to the many intelligent and customizable sensors with which UAVs are capable of being outfitted.

Damage assessment, relief, and rehabilitation have time sensitive needs, and UAVs are uniquely able to meet them. Exercises that historically took emergency response teams days or weeks to accomplish, such as search and rescue or monitoring exceptionally risky environments, have become nearly instantaneous with UAVs, reducing logistical and cost inefficiencies. And judging by current investment trends in the commercial drone industry, the economic and logistical advantages of this technology for data collection will multiply over the coming years.

Developing countries struggle with cost complexity and keeping up-to-date

Beyond critical and immediate data needs, UAVs can be (and are being) used in developing countries as tools to consistently digitize risk across their rapidly changing landscapes. The Zanzibar Mapping Initiative is a perfect example: it is the world’s most extensive mapping exercise to-date using commercial drones for a government-driven survey.

As a small island state with limited resources and significant development in need of documentation, Zanzibar opted to invest in geospatial innovation instead of contracting a traditional manned operation. The results of this ambitious endeavor have been transformative. The previous traditional aerial mapping in 2004 cost the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar approximately $2.5 million USD and delivered orthophotos with a resolution of 13-15cm. In contrast, the Zanzibar Mapping Initiative cost only $250,000 USD (an order of magnitude less!) and provided imagery of significantly higher quality at 2.5-7cm. This initiative is proof that UAVs have the potential to make risk assessment faster, cheaper, and better – and that high-resolution assessments can be conducted in new areas where it was previously prohibitively expensive or infeasible.

Emergency management includes drone management – whether countries realize it or not

UAVs offer vast benefits for emergency response and management – increasing speed, improving safety, reducing cost, and expanding reach. The Red Cross have been quick to champion this technology for relief efforts and recently launched a comprehensive drone disaster relief program to be piloted in the United States.

Cargo drone flights are further extending emergency management benefits of UAVs by supporting response, communications, and resilient supply chains in developing regions. The “Malawi Drone Corridor,” Africa’s first air corridor to test the use of UAVs in humanitarian missions, has been one of the greatest success stories to emerge from the continent, establishing a “test site for aerial scouting in crisis situations, delivering supplies and using drones to boost internet connectivity.” In Tanzania, the Lake Victoria Challenge – scheduled for October 2018 – aims to showcase advances in autonomous technologies that can make a significant difference in hard-to-reach communities and rural areas.

Countries can use drones to leapfrog, but they need to get the environment right.

Excitement generated by the potential of UAVs in DRM has played a critical role in creating environments that stimulate innovation. That said, UAV provision for emergency relief by volunteer hobbyists has at times led to chaos, largely due to inadequate management and a lack of clear operating regulations. It is thus paramount that preparation, procedures, and permits are established in order to constructively leverage UAVs for emergency management. Once these are adopted, local skills, capacity, and analytical tools can be generated, and UAV-related partnerships and networks will reap the many benefits of this burgeoning realm.

Flying robots: Collecting, delivering and analyzing geoinformation using UAVs –a technical session at the 2018 Understanding Risk Forum – will attempt to comprehensively tackle this subject with the aid of experts and end users in this emerging area of practice. Inspiring case studies will demonstrate how UAVs have supported DRM, the challenges faced, and how they have been overcome. This will be followed by a practical session summarizing the do’s and do not’s of managing risks, organizing data, and getting involved in the future of UAVs for DRM.

Edited by Jocelyn West, GFDRR